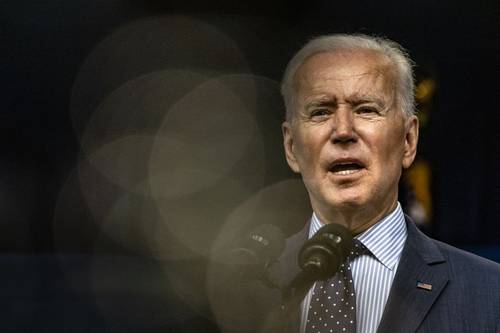

| President Biden plans to take a hard line with Russian President Vladimir Putin during their upcoming summit over a rash of ransomware attacks that hit critical U.S. companies. But it will probably take a lot more than that to get the attacks to stop, experts say. "The president is very determined on this, but the first thing Putin will do is say, 'prove it.' And he doesn't mean 'prove we did it.' He means 'prove you'll do something back,' " Jim Lewis, a cybersecurity expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and a former cybersecurity official in the State and Commerce departments, told me. The White House "[is] not taking any options off the table" as it mulls responses to a pair of major ransomware attacks from Russian criminal groups that sparked turmoil in the United States, spokeswoman Jen Psaki said. The first of those attacks against Colonial Pipeline strangled gas supplies in the southeastern United States. The second, against JBS, is threatening to affect U.S. beef and pork supplies. During their summit in Geneva later this month, Biden intends to tell Putin that "harboring criminal entities … that are doing harm to the critical infrastructure in the United States is not acceptable," Psaki said.  Vladimir Putin shakes hands with Vice President Biden during a meeting in 2011. (Alexander Natruskin/Reuters) | The attacks have placed Biden in an all-to-familiar conundrum for U.S. officials. For more than a decade they've condemned increasingly brazen Russian cyberattacks targeting companies and government agencies in the United States and abroad as well as digital influence operations aimed at undermining the 2016 U.S. elections and deepening U.S. political divisions. But they've never found a way to force Russia to rein in those attacks. A raft of increasingly harsh sanctions has also produced no change in Russia's behavior. And there's little reason to believe Putin will have a change of heart now. "They've been doing this for 20 years and nothing's ever happened except sanctions, which they're totally unfazed by," Lewis said. "The U.S. will have to decide whether it does nothing — and I'd include sanctions in the category of doing nothing — or if it wants to do something that puts more pressure on." For Lewis, the only response likely to rein in Russian cyberattacks is a proportional retaliatory cyberattack by the United States. Such an attack might, for example, cripple the computer infrastructure used by the criminal groups responsible for the Colonial Pipeline and JBS hacks, he said. Although those hacks were launched by criminal groups, experts generally agree that those groups work in Russian territory with at least the tacit approval of the Kremlin. Psaki underscored that point during yesterday's briefing, saying Biden "certainly thinks that President Putin and the Russian government ha[ve] a role to play in stopping and preventing these attacks."  President Biden speaks in Alexandria, Va. (Chris Kleponis/CNP/Bloomberg News) | Other experts agreed it will take more than harsh words to halt Russia-based ransomware attacks. Russia might rein in cybercriminals operating on its territory if it faced a concerted effort that included economic consequences from the United States and its allies — all of whom have an increasingly urgent interest in reducing ransomware attacks, Megan Stifel, executive director for the Americas at the Global Cyber Alliance nonprofit group and a former National Security Council cybersecurity official, told me. The Biden administration might organize such a joint pressure campaign with the 66 nations that signed the 2001 Budapest Convention, the main international treaty on cybercrime, she said. "The stakes are getting higher for everyone as we're becoming more interconnected," Stifel said. "The stakes are higher for the global community. We need to work the diplomatic side to say, 'this is not just our problem.' " And yet, the White House may have a better shot getting Russia to clamp down on ransomware than halting its other cyberattacks. There's effectively no chance, for example, that Russia will step back from major espionage-focused hacks, such as the SolarWinds campaign, which allowed its spy services to steal reams of secret documents from a slew of U.S. government agencies. That's partly because those hacks are extremely useful for the Kremlin's spy services. It's also because the United States and its allies also conduct espionage-focused cyber operations. When it comes to ransomware, however, Putin might be persuaded that the benefits of clamping down on it outweigh the benefits of letting it continue, Chris Painter, the State Department's top cybersecurity official during the Obama administration, told me. "It's going to be hard to get Russia or any country to stop doing espionage… [but] with criminal activity you might have a better chance," he said. "If [Putin] can take action that gets him some approval from countries around the world and doesn't cost him much, he might do that. Will it be long-lasting? Maybe not." | Share The Cybersecurity 202 |  |  |  | | |

No comments:

Post a Comment