“What if there was a way to detect fraud for SUD facilities?” plus 1 more |

| What if there was a way to detect fraud for SUD facilities? Posted: 03 Jun 2021 05:00 AM PDT The following is coauthored by Cecille Avila (@cecilleavila), Austin Frakt (@afrakt), and Melissa Garrido (@garridomelissa). Millions of Americans struggle with substance use disorder, with estimates suggesting as many as 1 in 13 people needed treatment in 2018. Between high demand for services and lack of regulation, this is an area of health care already rife with predatory behavior. Substance use disorder fraud was a significant problem before the COVID-19 pandemic, and it could potentially get even worse. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), more individuals reported an increase in substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic, and overdose deaths have gone up significantly. Now that vaccination rates are increasing and social distancing measures are being lifted throughout the United States, well-intentioned individuals or concerned family members may view rehabilitation facilities or treatment centers as a logical next step to address some of these issues. But it's not as easy as Googling "substance use disorder rehab facility near me" to find treatment centers that can provide appropriate — or even genuine — treatment. The amount of fraudulent behavior that has occurred in the past decade can make it feel as if there are equal numbers of results for substance use disorder treatment facilities and horror stories. In some cases, individuals have been sent out-of-state as part of elaborate and profitable patient brokering schemes that do not actually connect them to treatment. Some treatment facilities have profited off patients by overbilling for unnecessary drug tests. Treatment facilities with a known history of violations have continued to operate, resulting in the deaths of patients. In Florida, a man running sober homes was found to have coerced residents into prostitution. Using news articles and publicly available legal filings, it might be possible to identify potential warning flags for facilities by looking at their websites or asking certain informational questions, such as:

The list goes on, and it would be impossible for individuals to try and find answers for every facility in question in a reasonable amount of time. Perhaps what would be helpful is if there were an automated way — even a resource — that could guide people toward more trustworthy providers who offer appropriate addiction treatment. How? One potential approach could be to use insurance claims data to identify patterns that suggest fraudulent activity. For example, suspicious behavior might be detected through unusual frequencies of procedures (i.e., drug tests, including urinalysis), unusual numbers of patient encounters per specific providers, potentially unnecessary treatments, unbundled lab tests (instead of billing under a single code), duplicate or multiple billing, or upcoding (billing for more expensive procedures). However, flagging a single suspicious incident, such as high frequencies of tests or procedures, may reflect an overly cautious provider and not a fraudulent one. But perhaps a provider with a high rate of suspicious activities relative to its peers is more likely to be fraudulent. If nothing else, it could assist insurers, regulators, and law enforcement in focusing resources to scrutinize providers more likely to be engaged in illegal fraud. While using claims data to detect fraud can be helpful, it's not a perfect system. Claims data depends on what providers submit, so providers can get away with potentially problematic behavior if they don't bill insurers for it. Patient kickbacks, in which individuals receive both indirect and direct incentives to refer patients to certain facilities, is a significant problem in this industry and does not generate claims data. Facilities that benefit from patient kickbacks without raising any other flags could remain undetected. One challenge: An individual payor will only see or experience a subset of providers' behavior. Perhaps a pattern of fraud can only be reliably detected by tracking providers across multiple payors. Unfortunately, pooling data across insurers is difficult. Some data sets that do so (e.g., all-payer claims) do not identify providers, rendering them useless for the task. But a few resources exist that have data elements up to the task, such as those provided by FAIR Health or the Health Care Cost Institute, among others. Of course, accessing data is just the first step. The next is to develop and validate an algorithm to identify more likely fraudulent providers. Doing so could help reduce unethical provider behavior. While the COVID-19 pandemic dominated the news, the opioid epidemic did not fade away. Being able to connect individuals to appropriate and effective services is necessary to prevent even more harm from being done and without concern about falling victim to fraud. Research for this piece was supported by the Laura and John Arnold Foundation. The post What if there was a way to detect fraud for SUD facilities? first appeared on The Incidental Economist. |

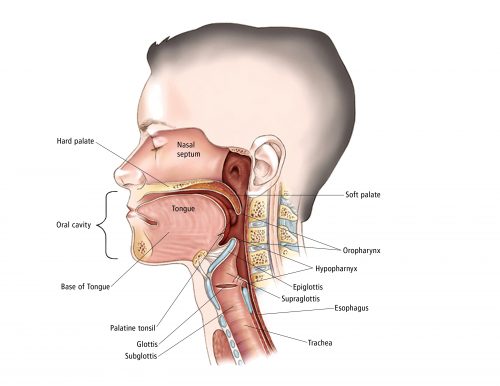

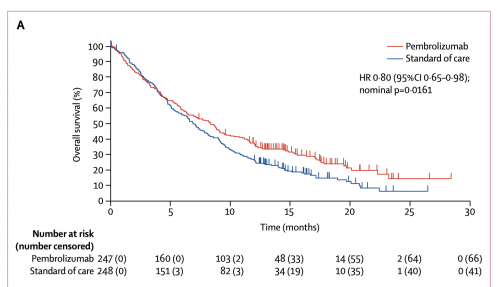

| Posted: 02 Jun 2021 05:30 AM PDT At the end of April, I received an end-stage diagnosis for my throat cancer. What this means is that although there’s no certainty about when I will die, neither I nor my physicians see a likely path leading to a cure. That doesn’t mean that there is no hope. We are working on a new plan of treatment with immunotherapy. In this update, I will explain what immunotherapy does. My cancer is an oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC).  Anatomy of the head and neck. The oropharynx is the region of the throat between the tongue and the epiglottis. In OSCC, the cells that line my throat in that region have started growing in an uncontrolled manner, forming a tumour. The first line of treatment for OSCC is radiation, and it is usually curative. But unluckily for me, my tumour survived radiation and quickly recurred. It’s now a hard lump, visible on the right side of my neck, with an ulcer inside my throat. Why is a lump in my throat a problem? In order of increasing severity, here is what the tumour does. First, I feel disfigured by the visible tumour. There is also pain, from the ulcer and because the tumour impinges on the nerves in my throat. The tumour is getting large enough to hinder my swallowing, which is already difficult because of the pain. I may have to go back to feeding through a tube. If the growth is unchecked, it will block my airway, although we can ‘fix’ that with a tracheotomy. Worst of all, a large tumour includes millions of cancer cells, and the more cells there are, the more likely it is that one or more will escape and seed metastatic tumours elsewhere in my body. These, as they grow, will shut down other body systems. This last process is what is most likely to kill me. In short, if possible, we want to get this thing out of me! Which is, of course, what cancer treatment is about. In essence, cancer can be treated with radiation, surgery, or medications. The 35 sessions of radiation I received last summer left my tumour unimpressed. More radiation would likely hurt me more than the tumour. I could have throat surgery, and if the surgeon completely removed the tumour and its local metastases, that would likely cure me. Unfortunately, my tumour is large and located at the centre of the base of my tongue. This means that the surgery would damage a great deal of tissue. I would likely lose my tongue and much of my larynx, so I would be unable to swallow or speak. The surgery would also damage my epiglottis, the flap of tissue that allows us to switch the throat from a tube delivering air to the lungs to one delivering food and water to the gut. If my epiglottis isn’t working, my lungs will get infected, leading to pneumonia. I would spend much of my post-surgery time in the hospital and I would likely die there. Think about that: would you want to have to die in a hospital during COVID, possibly alone, and unable to talk to anyone about what is happening to you? Two surgeons have now walked me through the consequences of surgery. Neither hid his relief when I declined the procedure. This leaves medication. Classical chemotherapies work by damaging the genes in the nuclei of cancer cells. The problem is that they hurt the rest of the body, too, just not as much. But recently, medical oncologists have been developing immunotherapies. The current plan is for me to start treatment with a drug called pembrolizumab.* To explain how this drug works, let’s take a step back and ask why cancer happens. Cancer happens because something damages the machinery in a cell that regulates the cell’s reproduction, leading it to grow uncontrollably. But that’s not enough to produce a tumour. The tumour also needs to escape the body’s immune system. The immune system’s T-cells fight microbial pathogens, and they also search for and destroy cancer cells. The T-cells are like the police. If you are a cell, so long as you don’t reproduce more than you are supposed to, then no one gets hurt. Which is great, except that having armed patrols roaming the body poses its own danger. If the T-cells get too aggressive and start attacking normal body tissues, we have an autoimmune disease. To prevent this, the body has evolved mechanisms that can suppress the T-cells. One of these is called the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. PD-1 is a receptor protein on the surface of a T-cell for programmed cell death. It is an off-switch on the T-cell. If another cell can bind to this receptor using a protein called PD-L1, the T-cell kills itself. But this, unfortunately, provides an opportunity that the tumour can exploit. If the tumour gets a mutation that allows it to express a lot of PD-L1, it can escape the T-cell police and continue its uncontrolled reproduction. Here is where pembrolizumab comes in. The molecule prevents the tumour from using the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway to shut the T-cells down. If the drug can do this, the T-cells will attack the tumour, which sometimes just ‘melts away.’ Some people have reactions to the drug, including inflammations that might be caused by overactive T-cells. Fortunately, these side effects are typically much less severe than those of older chemotherapies. Sounds great, no? Well… here are the results from the KEYNOTE-048 trial, comparing pembrolizumab against the previous standard of care. The patients have recurrent head and neck cancer, like me. The horizontal axis is the time since the initiation of treatment. The vertical axis is the proportion of patients who are still alive at that time.  Survival curves: Pembrolizumab vs Cetuximab with chemotherapy. Notice that half of the pembrolizumab patients are dead by 9 months. Pembrolizumab does better relative to standard care. But in absolute terms, the treatment doesn’t accomplish much. Why doesn’t immunotherapy work better? My cute story above oversimplified the immune system. The system includes a zillion other mechanisms, an alphabet soup of pathways, each seemingly there to correct the malfunction of some other pathway. Here is an animation that illustrates how the immune system functions. The immune system is a reductio argument against intelligent design: if it had a designer it must have been a committee of lunatic clockmakers, who spoke no common language. Immunotherapy doesn’t work that well because we don’t know what we are doing. You could not pay me enough to be an immunologist. We are in an odd historical moment in oncology. On the one hand, we have enough data that I can foresee my life expectancy with some confidence. Twenty years ago, I couldn’t. On the other hand, we can’t reliably cure this disease. I hope my great-grandchildren will be shocked to learn that people used to die from cancer. What matters, however, is the survival curve. Even with my best treatment option, I don’t have much time. So be it. That time is where the hope is. I need to think hard and make good choices about what to do with it. *Where do these crazy drug names come from? There is actually a system to it (h/t, David States). To read the Cancer Posts from the start, please begin here. The post Cancer Journal: Immunotherapy first appeared on The Incidental Economist. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from The Incidental Economist. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

No comments:

Post a Comment