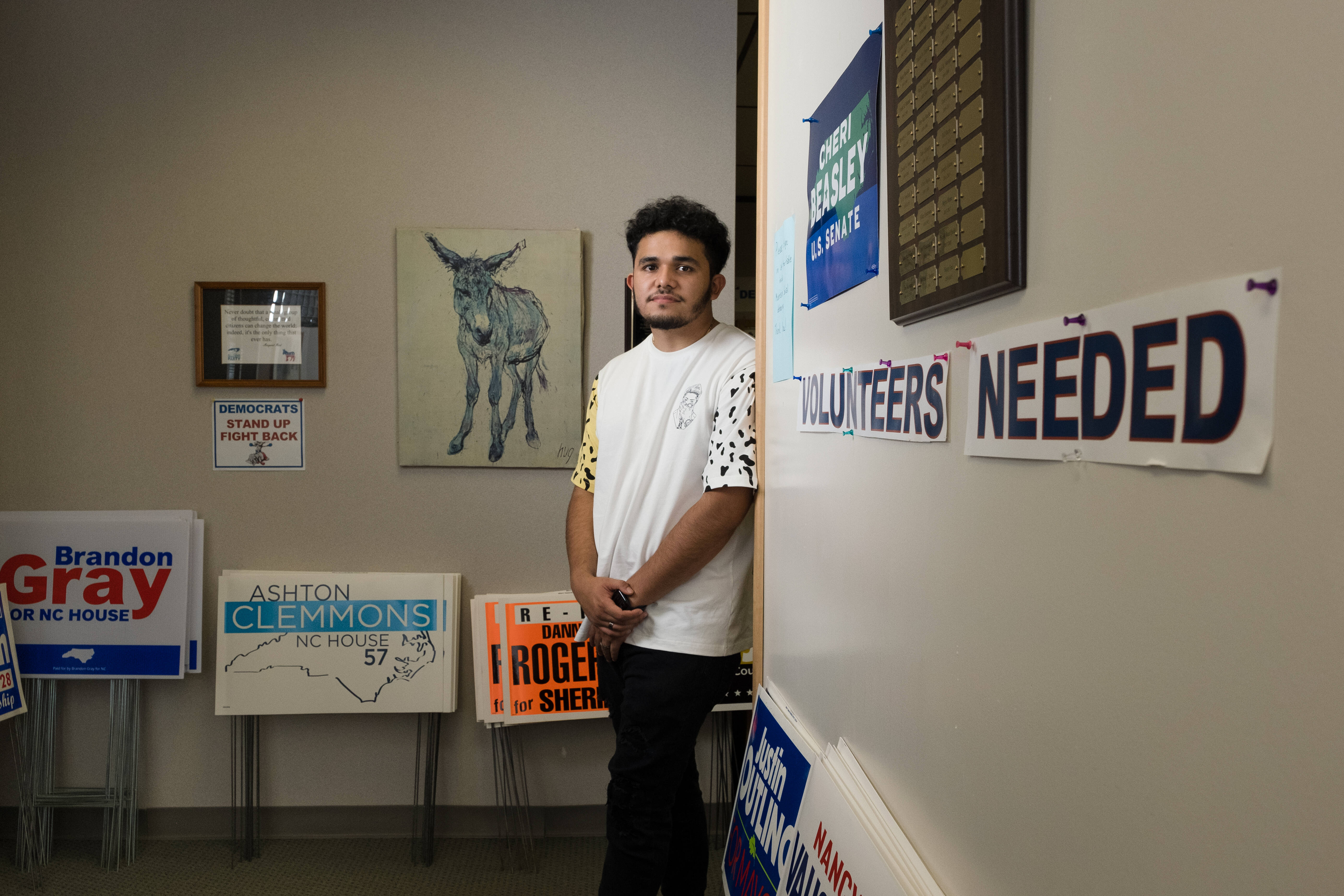

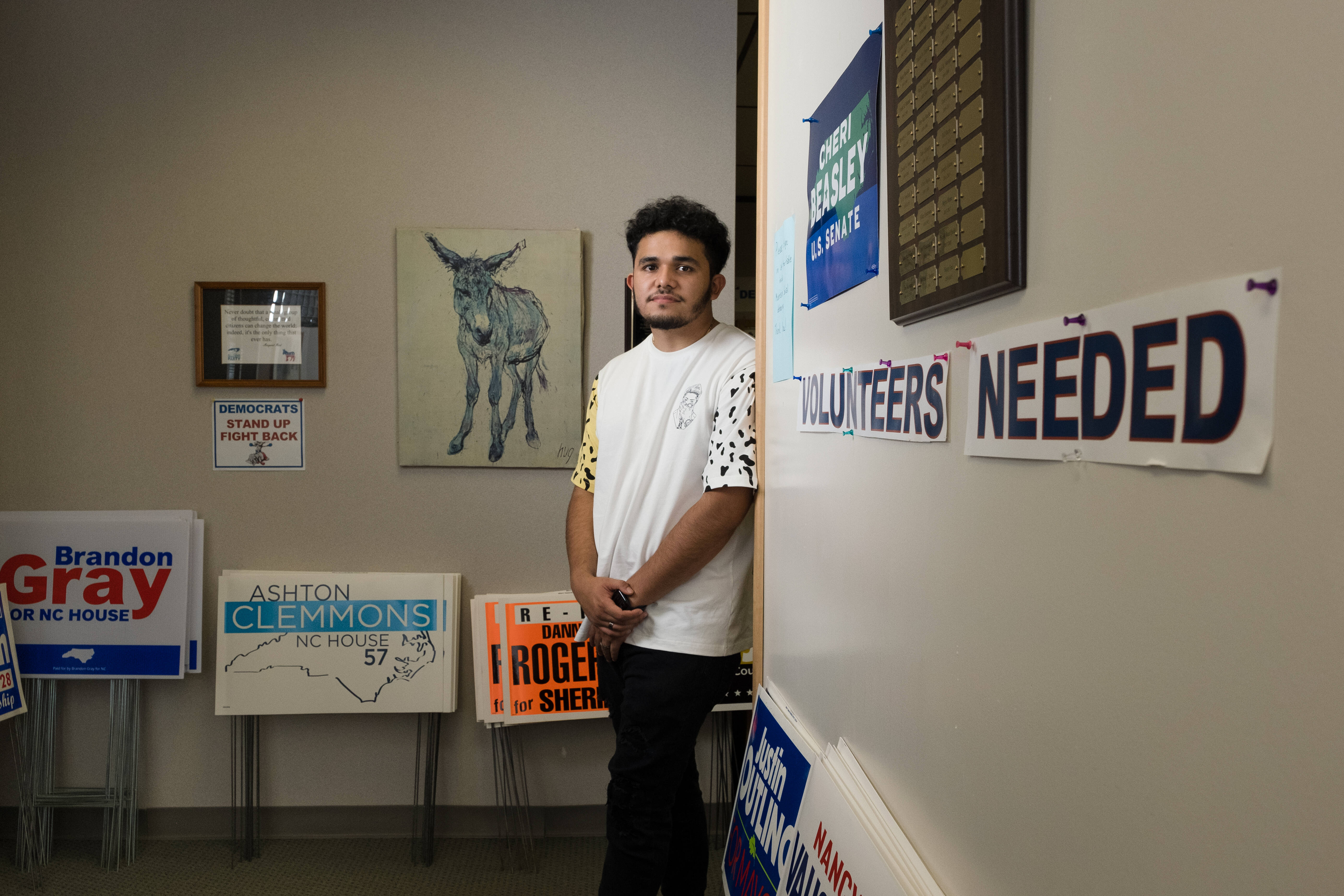

| Once again, President Biden must go it alone. So far in his presidency, he and Democrats in Congress have failed to strike deals to protect voting rights, protect abortion rights and expand government services — and now, they've likely failed to pass legislation reducing enough greenhouse gas emissions to avoid the most catastrophic effects of climate change. Biden has been repeatedly blocked by Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) on all of this, and in a Senate where Democrats have the majority by only a tiebreaking vote, that's enough to effectively kill any legislation. So now, The Post's Tony Romm, Jeff Stein and Ashley Parker report, Biden is considering declaring a climate emergency to try to curb gas and oil drilling and have federal agencies focus on developing renewable power. He could even use emergency powers to require carmakers to pivot more toward electric vehicles. "The president made clear that if the Senate doesn't act to tackle the climate crisis and strengthen our domestic clean energy industry, he will," a White House aide told my colleagues. Biden is going to talk about the need to take action on climate change Wednesday. It's not clear whether his actions alone will be enough — to reach his goals of halving U.S. emissions by the end of the decade, or to convince disillusioned Democrats that he's doing all he can. Walmart supports career growth & opportunity. 75% of store, club and supply chain management started as hourly associates. At Walmart, there is a path for everyone. Learn more. | |  | | | | Speaking of disillusioned Democrats The Post's Danielle Paquette recently visited with college-age Democratic activists in North Carolina, a critical swing state for the party. These young activists feel as if the president and their party haven't fought hard enough for the causes that are important to them, such as climate change. Albaro Reyes-Martinez, a senior at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro and president of the College Democrats, told her: "It gets harder when we keep winning elections and nothing is happening. Not everyone's going to be like: 'Okay, yeah, let's go vote for them again.'"  Albaro Reyes-Martinez. (Cornell Watson for The Washington Post) | The messy legal landscape on abortion This month alone, abortion was legal then illegal then legal again in Louisiana. It could change again soon, when another judge will rule on whether that state's trigger law that bans most abortions now that the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade should stand. Scenes like that are playing out across the country in the more than a dozen states that have trigger laws, some of them decades or even more than a century old. The uncertainty is really difficult for patients, abortion rights supporters say. "We are still getting a lot of desperate phone calls from women who are angry or sobbing," Kathaleen Pittman, who runs an abortion clinic in Shreveport, La., told The Post's Katie Shepherd. "They seem so totally beaten down because they have been trying to access care and, in one moment, it is available in a few weeks. The next minute, it may not ever be available here." Abortion rights activists are mining state constitutions to challenge these laws. North Dakota, for example, says its residents have a constitutional right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and abortion rights lawyers are arguing that state's trigger law violates that. In Idaho, abortion rights activists are arguing that an abortion ban violates that state's constitution, which they say guarantees a right to privacy. "It boils down to the right to bodily autonomy," Elizabeth Nash, with the pro-abortion-rights research group Guttmacher Institute, told me. Abortion opponents argue that the Supreme Court explicitly paved the way for states to set their own laws about where to draw the line. It could take years for these legal battles to resolve in court, and there may be lots of flip flops before then. What is the Electoral Count Act, and why might Congress change it? More than a year after the attack on the U.S. Capitol, Congress has passed precisely zero legislation to prevent it from happening again. But there's one narrow area that has bipartisan support: limiting the already limited role that Congress plays in deciding the president of the United States. That process is governed by the Electoral Count Act, a 135-year-old law that is supposed to guide Congress if the results of a state's electors are in question. (Once states certify their results from a presidential election, Congress certifies states' results.) But most legal experts say the confusing law opens up the process for bad actors to take control. The Jan. 6 committee says Donald Trump's lawyers muddied the law to pressure Vice President Mike Pence to throw out results in states Trump lost.  Pence presides over the certification of state electoral counts on Jan. 6, 2021. (J. Scott Applewhite/AP) | So a bipartisan group of senators wants to fix it. They are proposing legislation this week that would clarify that the vice president's role in certifying states' results is merely ceremonial and make it harder for lawmakers to challenge the results of a state. They also want to make it so states can't change their electors after Election Day, report The Post's Leigh Ann Caldwell and Theodoric Meyer. (Because Trump also tried to pressure state legislators to do just that.) My colleagues report that this has a pretty good chance of passing the Senate, which is the biggest hurdle these days to something becoming law. |

No comments:

Post a Comment