Mises Wire |

- Do "Inflationary Expectations" Cause Inflation? Contra Krugman, the Answer Is No

- Sovereign Immunity Is Antilaw: The State Must Make Restitution to Its Victims

- New Covid Study Shows Lockdown-Heavy States Had Some of the Worst Health Results

- Fetter the Radical

- And Now for a Really Bad Response to Political Calamity: Autarky

- The Fed Wanted Inflation, Now They Have No Idea What to Do

- Political Upheaval Is Not Threatening “Our Democracy.” Our Democracy Is.

- The Wrong Elites

- How Russia Uses Immigration and Naturalization to Grow State Power

- Fighting Back: My Legal and Ethical Battle against Covid Mandates

- How Fully Private, No-Insurance Hospitals Help the Common Man

- The Nature of Man and His Government

- Behind Klaus Schwab, the World Economic Forum, and the Great Reset: Part 5

- Instead of War, Russia, Ukraine and Their Allies Should Try the Free Market

- The Fed Can't Fix the Economy, but It Can Break It

- If Ukraine Joins the EU, It Will Be the Poorest Member by Far

- Deflation: Bad for the Government, Good for Producers and Consumers. What's Not to Like?

| Do "Inflationary Expectations" Cause Inflation? Contra Krugman, the Answer Is No Posted: 15 Apr 2022 05:00 AM PDT Paul Krugman recently wrote that the reason we see high inflation is that people mistakenly believe inflation is in our future and act accordingly. This reasoning is false. Original Article: "Do "Inflationary Expectations" Cause Inflation? Contra Krugman, the Answer Is No" This Audio Mises Wire is generously sponsored by Christopher Condon. | ||

| Sovereign Immunity Is Antilaw: The State Must Make Restitution to Its Victims Posted: 15 Apr 2022 04:00 AM PDT The doctrine of sovereign immunity1 is the antithesis of libertarianism.2 Immunity from the consequences of its actions makes the state (i.e., those who work for it) so very dangerous. A private party who causes manifest measurable harm to others can be sued, if not prosecuted, for that harm. Sovereign immunity short-circuits this vital feedback mechanism that provides strong incentives to refrain from further such harm. To the extent that state agents cannot be sued, and may even be rewarded, for bad behavior, they will continue to harm their citizens with impunity. The removal of sovereign immunity is necessary if no one is to be "above the law." Currently, in the unlikely case that someone does successfully "fight city hall," the guilty parties are seldom the ones who pay. As a case in point, the $27 million settlement paid to the family of George Floyd came not from the pocket of the police officer the court ruled guilty of Floyd's death3 or the police high command that authorized the restraint technique applied with deadly result, but rather from the Minneapolis taxpayers, none of whose knees were on Floyd's neck.4 Since the officer in question presumably did not have $27 million with which to pay such a settlement, removing sovereign immunity would require all those working on behalf of the government to carry liability insurance. If physicians must carry malpractice insurance and employees in fields ranging from banking to janitorial services must be bonded, for what reason should government officials be spared such requisites? While these insurance costs would likely discourage many people from seeking government employment, anyone who considers our current government to be too large and powerful would consider this outcome desirable. What makes ending immunity necessary is that the cash nexus so characteristic of private economic transactions is not present in the public sector. In the private sector, if I am not satisfied with a product I purchase, I have several options: seeking a refund, exchanging my defective product for a nondefective one, or ceasing to do business with those merchants and dissuading as many people as I can from transacting with them as well. Those potential consequences are likely to bring most businesses in line. This option is basically not available in any meaningful way for government-provided services, since we are forced to pay through taxation for what government provides regardless of whether we are satisfied with it or not, or even whether we use it or not. Let's look at what is universally seen as the most important function of the government—protection of life and property. In the spring and summer of 2020, mayors of dozens of large American cities failed to fulfill this most important function, ordering their police to stand down as people rioted, causing dozens of deaths and billions of dollars in property damage. In New York City, for instance, "not only did the city brutalize protesters exercising their First Amendment right to assemble, but it also stood by as throngs of nonpolitical actors rampaged the city's storefronts."5 Risks to residents and property damage in and around protests paled in comparison to the widespread looting in New York, yet the police responses to nonideological rioting were markedly slower. Would then mayor Bill de Blasio and his police commissioner have been so derelict in their most important duty had they known they would have had to pay damages out of their own pockets?6 A second example highlights the governmental response to covid-19. Had key public-health officials, governors, and mayors not been immune from liability for the consequences of their policies, we might not have seen them arrogantly stand between doctors and their patients by suppressing legally approved drugs such as ivermectin and thus increase the number of deaths and hospitalizations caused by a virus spawned in US government–funded labs.7 Nor would they have severed people from their means of sustenance through lockdown policies based much more on politics than on science. They are at least as guilty of malpractice as any doctors successfully sued for their errors. Finally, the state has managed to confer its own sovereign immunity on private-sector actors. Traditionally, companies could be sued for irreversible harms caused by their defective products. For example, Vioxx, a pain-relief and anti-inflammatory drug produced by Merck, was found to have played a role in causing twenty-seven thousand heart attacks. Merck was sued and settled for $4.85 billion (roughly 12 percent of its annual revenue). This result was consistent with the principle that those who harm others have to compensate their victims. This principle appears to have been completely jettisoned with regard to vaccine manufacturers. Breaking the link between causing harm and making restitution has been enshrined in law by the 1986 National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act (NCVIA). While claiming that one of its goals is to "ensure the production and procurement of safe and effective vaccines," the act's provision that "no vaccine manufacturer shall be liable in a civil action for damages arising from a vaccine-related injury or death" does not exactly create incentives conducive to that outcome. We want to incentivize the production not of any and all vaccines, but of safe and effective vaccines. If manufacturers make vaccines that are unprofitable because of the insurance premiums that must be paid to cover the liability for those injured by those vaccines, then those particular vaccines have failed the market test. For that reason, polio-vaccine pioneer Dr. Albert Sabin, who cannot be dismissed by any honest and sane person as an "antivaxxer," opposed laws like the NCVIA. In the words of economist Barry Brownstein, "the best way to ensure vaccine safety is to expose pharmaceutical companies to the full costs of any mistake and not let any company without proper insurance near a human body."8 This principle that no one should be above the law applies universally. If car manufacturers are held liable for faulty cars that lead to excess injuries and deaths, you will get fewer cars, but safer cars. If vaccine manufacturers are held liable for faulty vaccines that lead to injuries and deaths, you will get fewer vaccines, but safer vaccines. And if those charged with enacting and enforcing laws can be held liable for failure to protect and violation of rights, you will get fewer laws, but more rights. While the principle is clear, the problem is the implementation. Now there is the need for libertarian legal scholars to develop ways of implementing these principles. This will not be simple, as many cases will be far from black and white. In addition, we will need many more judges who have internalized this principle than are likely to be turned out by our law schools in their current state. Nonetheless, even imperfect implementation should prove far superior to the current situation of nearly total government immunity. If we can accomplish that, we can begin the process of undoing at least a century of damage state that actors not bound by law have done to this country.

This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||

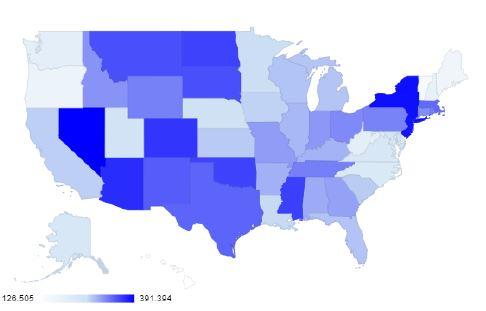

| New Covid Study Shows Lockdown-Heavy States Had Some of the Worst Health Results Posted: 14 Apr 2022 04:30 PM PDT As hard as it is to believe, the Chinese regime is still employing a "zero covid" strategy and claims it can eradicate covid entirely through lockdowns and vaccinations. China's draconian, nightmarish, near-total lockdown policy—which is notably still "necessary" in spite of widespread vaccination—has recently been revived in Shanghai where residents are now struggling to find food. But the regime has only doubled down on the policy, with Chinese President Xi Jinping declaring that "persistence is victory." This approach has no basis in any actual science, however, and contradicts decades of epidemiological research condemning lockdowns. Moreover, a 2021 joint study from USC and the Rand Corporation concluded "excess mortality increases" following "the implementation of SIP [shelter-in-place] policies." This week, a new study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that the states with the harshest lockdowns tended to perform the worst in a composite measure of mortality, economic performance, and education. The states that performed the best were in many cases states where lockdowns were weak or nonexistent, with Utah and Nebraska at the top of the list. The study, authored by Phil Kerpen, Stephen Moore, and Casey B. Mulligan, also concluded that antilockdown Florida, Arkansas, West Virginia, and Utah "were outliers" that performed unexpectedly well compared to their neighbors. Prolockdown California, Illinois, New Mexico, and Colorado, on the other hand, performed more poorly than their neighbors. The chief value of the report is that it takes economic, educational, and health variables and normalizes them across states. For example, it's difficult to meaningfully compare economies when some states are far more reliant on service industries than others. In this case, the authors find the "combined economic performance" for states taking the nature of each state's economy into account. By this metric, the states that performed the best during the pandemic were lockdown-light states Montana, South Dakota, Nebraska, Idaho, and Utah. The states with the worst outcomes were lockdown-heavy Hawaii, New jersey, Connecticut, New York, and Illinois. On the matter of education—which the authors note is closely tied to both economic performance and mortality in the longer term—the authors look at bans on in-person education, state by state, and presumed resulting "learning loss." In this case, the best performers were Wyoming, Arkansas, Florida, South Dakota, and Utah. The worst performers were California, Oregon, Maryland, Washington, and Hawaii. Of course, if faced with statistics such as these, lockdown advocates are likely to admit that lost educational opportunities and lost economic prosperity are unfortunate. But, they will say education and property rights had to limited in the name of preventing mortality and protecting "public health." So what do we find when examining actual mortality and health outcomes? In this case, the authors controlled for key health variables like the prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and old age. Adjusting for these, lockdown-heavy states did, in fact, perform well with Vermont, Hawaii, Maine, Oregon, and New Hampshire coming in at the top. But lockdown-heavy states in this case were also among the worst performers with Nevada, New York, New Jersey, Arizona, and Colorado coming in at the bottom of the list. Moreover, this measure emphasizes just how irrelevant lockdowns can be when looking at mortality outcomes. For example, if we look beyond just the top and bottom five in the mortality rankings, we find some interesting comparisons. Age and Metabolic Health Adjusted COVID-Associated Deaths Per 100K Population (Updated March 9): Adjusting for age and obesity, Florida and Michigan are virtually identical in spite of the fact Michigan under governor Gretchen Witmer locked down long and hard. Florida by contrast is known for abandoning both lockdowns and mask mandates early. The state of Georgia—which was accused of embracing "human sacrifice" when it abandoned lockdowns early on—ranks better than much of New England (i.e., Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island) which was notable for harsh covid mandates. Rankings that fail to adjust for obesity and age, of course, miss key factors, and this could be seen in the fact that unadjusted covid outcomes tend to be especially poor in the Deep South. But the Deep South is also where obesity rates have long been among the highest, reflecting poor health outcomes in a variety of issues. Meanwhile, we should generally expect the best health outcomes from western states (excluding New Mexico, which is a regional outlier in terms of obesity) where residents tend to be thinner and in better health. Residents are generally in better general health in New England as well. Yet, once we adjust for these variables, the usual patterns don't hold up at all. Instead we find no clear connection at all between the length and severity of mandates and mortality outcomes. Of course, even if lockdowns states were shown to be reliably and indisputably among those states with the best health outcomes, that would still not justify the forced closure of businesses and violations of basic human rights like the right to seek income and the right to travel. Basic human rights don't disappear simply because an unelected health workers declares an emergency. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||

| Posted: 14 Apr 2022 12:00 PM PDT [This is Murray Rothbard's introduction to Frank A. Fetter's Capital, Interest, and Rent.] Frank Albert Fetter (1863–1949) was the leader in the United States of the early Austrian school of economics. Born in rural Indiana, Fetter was graduated from the Indiana University in 1891. After earning a master's degree at Cornell University, Fetter pursued his studies abroad and received a doctorate in economics in 1894 from the University of Halle in Germany. Fetter then taught successively at Cornell, Indiana, and Stanford universities. He returned to Cornell as professor of political economy and finance (1901–11) and terminated his academic career at Princeton University (1911–31), where he also served as chairman of the department of economics. Fetter is largely remembered for his views on business "monopoly" (see his Masquerade of Monopoly [New York: Harcourt, Brace and Co., 1931]). But long before he published his work on monopoly in the 1930s, he developed a unified and consistent theory of distribution that explained the relationship among capital, interest, and rent. While Fetter's theoretical work, like much of capital and interest theory in recent decades, has been generally neglected, much of it is still valuable and instructive today. In my opinion, microeconomic analysis has a considerable way to go to catch up to the insight that we find in Fetter's writings in the first decade and a half of this century. Apart from his two lucidly written treatises (The Principles of Economics [New York: The Century Co., 1904]; and Economic Principles [New York: The Century Co., 1915]), Fetter's major contributions to distribution theory appeared in the series of journal articles and shorter papers that I have collected to form this volume. It was difficult for me to classify Fetter's work into the categories of "capital," "rent," and "interest," because his was an unusually systematic and integrated theory of distribution, all areas of analysis being interrelated. Fetter's point of departure was the Austrian insights that (1) prices of consumer goods are determined by their relative marginal utility to consumers; and (2) that factor prices are determined by their marginal productivity in producing these consumer goods. In other words, the market system imputes consumer goods prices (determined by marginal utility) to the factors of production in accordance with their marginal productivities. While the early Austrian and neoclassical schools of economics adopted these insights to explain prices of consumer goods and wages of labor, they still left a great many lacunae in the theories of capital, interest, and rent. Rent theory was in a particularly inchoate state, with rent being defined either in the old-fashioned sense of income per year accruing to land, or in the wider neo-Ricardian sense of differential income between more and less productive factors. In the latter case, rent theory was an appendage to distribution theory. If one worker earns $10 an hour and another, in the same occupation, earns $6, and we say that the first man's income contains a "differential rent" of $4, rent becomes a mere gloss upon income determined by principles completely different from those used to determine the rent itself. Frank Fetter's imaginative contribution to rent theory was to seize upon the businessman's commonsense definition of rent as the price per unit service of any factor, that is, as the price of renting out that factor per unit time. But if rent is simply the payment for renting out, every unit of a factor of production earns a rent, and there can be no "no-rent" margin. Whatever any piece of land earns per year or per month is rent; whatever a capital good earns per unit time is also a rent. Indeed, while Fetter did not develop his thesis so far as to consider the wage of labor per hour or per month as a "rent," it is, as becomes clear if we consider the economics of slavery. Under slavery, slaves are either sold as a whole, as "capital," or are rented out to other masters. In short, slave labor has a unit, or rental, price as well as a capital value. Rent then becomes synonymous with the unit price of any factor; accordingly, a factor's rent is, or rather tends to be, its marginal productivity. For Fetter the marginal productivity theory of distribution becomes the marginal productivity theory of rent determination for every factor of production. In this way, Fetter generalized the narrow classical analysis of land rent into a broader theory of factor pricing. But if every factor earns a rent in accordance with its marginal product, where is the interest return to capital? Where does interest fit in? Here Fetter made his second vital and still unappreciated contribution to the theory of distribution. He saw that the Austrian Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, in the second volume of his notable Capital and Interest, inconsistently returned to the productivity theory of interest after he had demolished that theory in the first volume. After coming to the brink of replacing the productivity theory by a time-preference theory of interest, Böhm-Bawerk withdrew from that path and tried to combine the two explanations — an eclecticism that capital and interest theory (in its "real" form) has followed ever since. Fetter approached the problem this way: If every factor earns a rent, and if therefore every capital good earns a rent, what is the source of the extra return for interest (or "long-run normal profit," as it is sometimes called)? In short, if a machine is expected to earn an income, a rent, of$ 10,000 a year for the next ten years, why does not the market bid up the selling price of the machine to $100,000? Why is the current market price considerably less than $100,000, so that in fact a firm that invests in the machine earns an interest return over the ten-year period? The various proponents of productivity theory answer that the machine is "productive" and therefore should be expected to earn a return for its owner. But Fetter replied that this is really beside the point. The undoubted productivity of the machine is precisely the reason it will earn its $10,000 annual rent; however, there is still no answer to the question why the market price of the machine at present is not bid high enough to equal the sum of expected future rents. Why is there a net return to the investor? Fetter demonstrated that the explanation can only be found by separating the concept of marginal productivity from that of interest. Marginal productivity explains the height of a factor's rental price, but another principle is needed to explain why and on what basis these rents are discounted to get the present capitalized value of the factor: whether that factor be land, or a capital good, or the price of a slave. That principle is "time-preference": the social rate at which people prefer present goods to future goods in the vast interconnected time market (present! future goods market) that pervades the entire economy. Each individual has a personal time-preference schedule, a schedule relating his choice of present and future goods to his stock of available present goods. As his stock of present goods increases, the marginal value of future goods rises, and his rate of time-preference tends to fall. These individual schedules interact on the time market to set, at any given time, a social rate of time-preference. This rate, in turn, constitutes the interest rate on the market, and it is this interest rate that is used to convert (or "discount") all future values into present values, whether the future good happens to be a bond (a claim to future money) or more specifically the expected future rentals from land or capital. Thus, Fetter was the first economist to explain interest rates solely by time-preference. Every factor of production earns its rent in accordance with its marginal product, and every future rental return is discounted, or "capitalized," to get its present value in accordance with the overall social rate of time-preference. This means that a firm that buys a machine will only pay the present value of expected future rental incomes, discounted by the social rate of time-preference; and that when a capitalist hires a worker or rents land, he will pay now, not the factor's full marginal product, but the expected future marginal product discounted by the social rate of time-preference A glance at any prominent current textbook will show how far economics still is from incorporating Fetter's insights. The textbook discussion typically begins with an exposition of the marginal productivity theory applied to wage determination. Then, as the author shifts to a discussion of capital, "interest" suddenly replaces "factor price" on the y-axis of the graph, and the conclusion is swiftly reached that the marginal productivity theory explains the interest rate in the same way that it explains the wage rate. Yet the correct analog on the y-axis is not the interest rate but the rental price, or income, of capital goods. The interest rate only enters the picture when the market price of the capital good as a whole is formed out of its expected annual future incomes. As Fetter pointed out, interest is not, like rent or wages, an annual or monthly income, an income per unit time earned by a factor of production. Interest, on the contrary, is a rate, or ratio, between present and future, between future earnings and present price or payment. Fetter's theory makes it impossible to say that capital "earns," or generates an interest return. On the contrary, the very concept of capital value implies a preceding process of capitalization, a summing up of expected future rental incomes from a good, discounted by a rate of interest. Rent, or productivity, and interest, or time-preference, are logically prerequisite to the determination of capital value. Frank A. Fetter's earliest article in this collection, a review of Frank W. Taussig's Wages and Capital: An Examination of the Wages Fund Doctrine (New York: D. Appleton, 1896), was written in 1897 and sets the pace for the articles in the first part of this book. Here Fetter criticized Taussig's attempt to revive the classical notion of the "wage fund." Rather than attempting to explain aggregate wage payments, Fetter recommended explaining individual wage rates. Fetter's first full-length article on capital was his "Recent Discussion of the Capital Concept" (1900). In it he compared the theories of capital offered by Böhm-Bawerk, John Bates Clark, and Irving Fisher. Fetter did less than full justice to Böhm-Bawerk's subtle insistence on the defects of the idea of capital as merely a fund, especially in comparing or measuring concrete capital goods that differ from each other. Above all, Fetter, in properly concentrating on a fund of capital value as an attribute of all durable productive goods, never fully realized the importance between land (the original producer's good) and capital goods (created or produced producer's goods). In fact, Fetter's idea of capital as a fund of value and the Austrian view of capital as concrete capital goods are not inconsistent; they play roles in different areas of capital theory. Of special interest is Fetter's charge that Böhm-Bawerk's intention was to establish a labor theory of property in capital goods. Furthermore, when Fetter declared that Böhm-Bawerk was inconsistent in classifying man-made improvements permanently incorporated into the land as "land" itself, he apparently did not realize that for Austrian economists the crucial criterion for classifying a good as "land" is not its original nature-given state but its permanence as a resource (or, more precisely, its nonreproducibility). Goods that are permanent, or nonreproducible, earn a net rent, whereas capital goods, which have to be produced and maintained, only earn a gross rent, absorbed by costs of production and maintenance. Here is a vital distinction between land and capital goods that Fetter completely misunderstood (see my Man, Economy, and State, 2 vols. [New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1962], 2:502–4). Fetter, however, took his stand squarely with Böhm-Bawerk and against Clark when he denied that capital is a permanent fund and that production ever becomes "synchronous," thereby eliminating the time dimension between input and output. This same controversy was to reappear dramatically in the 1930s in publications of Frank H. Knight (advancing the Clark position) and those of Friedrich A. Hayek and Fritz Machlup (representing the Austrian view). On the other hand, Fetter praised Irving Fisher's theory of capital (The Rate of Interest: Its Nature, Determination, and Relation to Economic Phenomena [New York: Macmillan Co., 1907]) in places where it deviated from the Austrian view and criticized it where it conformed to the Austrian position. Thus, Fisher's distinction between capital and income (based on the differences between stock and flow measurements) is commended because it eliminates the need for distinguishing between land and capital goods. On the other hand, Fetter objected to Fisher's highly sensible insistence that the concept of concrete physical capital goods is logically prerequisite to the concept of abstract capital as a fund of value. Furthermore, Fetter objected to the Austrian view, also in Fisher, that capital goods are way stations on the path to producing more consumer goods, and that they are therefore "used up" in production. Fetter cited machines and land ("natural agents") as goods that do not advance toward the status of consumer goods. But machines advance toward consumer goods precisely by being impermanent, that is, by being used up in the march of production toward the goal of consumption; and the fact that land is not used up in this way is precisely the reason for distinguishing it from capital goods. In his 1902 review of Böhm-Bawerk's Einige strittige Fragen der Capitalstheorie Fetter quite properly pointed to the major textual contradiction in Böhm-Bawerk's theory of interest: Böhm-Bawerk's initial finding that interest stems from time-preference for present over future goods is contradicted by his later claim that the greater productivity of roundabout production processes is what accounts for interest. However, when criticizing Böhm-Bawerk's productivity theory of interest, it was not necessary for Fetter to dismiss Böhm-Bawerk's important conception of roundaboutness or the period of production. Roundaboutness is an important aspect of the productivity of capital goods. However, while this productivity may increase the rents to be derived from capital goods, it cannot account for an increase in the rate of interest return, that is, the ratio between the annual rents derived from these capital goods and their present price. That ratio is strictly determined by time-preference. "The Nature of Capital and Income" (1907) offered a review of Irving Fisher's book of the same title. Fetter hailed Fisher's use of the capitalization concept of capital as well as Fisher's abandonment of his previous view that the stock/flow concept of capital and income applied to the same concrete goods. Here, Fisher shifted to an abstract and generalized conception of stocks and flows. But, as Fetter noted, this very abstraction rendered the whole stock/flow dichotomy untenable. Fisher's treatment of income as strictly psychic income, to the virtual exclusion of money income, is properly criticized, as is the corollary that only consumption is income, and therefore capital gains are not income and should not be subject to an income tax. Finally, Fetter, who had himself been working on an integrated theory of income distribution, found that Fisher's theory of capital and income had an ad hoc flavor because it had been developed separately from the remainder of Fisher's distribution theory. In "Are Savings Income — Discussion?" (1908), Fetter elaborated on his criticism of Fisher's view that savings, or rather additions to capital, are not income, and that the term income should be limited to consumption expenditure only. Fetter correctly pointed out that Fisher confused the concept of ultimate psychic income, which indeed consists only of consumption, with the concept of monetary incomes acquired in the market, which are partially saved and partially consumed. Two decades later (1927) Fetter returned to the theory of capital in his contribution to the Festschrift honoring John Bates Clark. In the course of reviewing Clark's contributions to the theory of capital, Fetter praised Clark for treating capital as a fund rather than as an array of heterogeneous capital goods and for offering a general definition of rent as the income from all capital goods and not just the income from land. Böhm-Bawerk is criticized once again for clinging to the identification of capital and interest (instead of realizing how interest permeates the entire time-value market), but this cogent criticism is again misleadingly linked to an attack on Böhm-Bawerk for maintaining a distinction between land and capital goods. In this article, F. W. Taussig is criticized for allegedly maintaining that only land, and not capital, is productive. But here Taussig was not simply in the throes of the labor theory of value; rather, he was adopting the subtle Böhm-Bawerkian insight that, while capital goods are evidently productive, they are not ultimately productive, for they have to be produced and reproduced by labor, land, and time, so that capital goods earn gross rent, but not net rents, which go only to labor and land factors. Hence again we encounter the importance of the land-capital goods distinction. As for interest, it is entirely the result of time-preference; in the case of a capital good, interest depends on first producing the capital good by combining labor and land and then on reaping the fruits of this combination at a later time. The very distinction between land and capital goods so resisted by Fetter was thus used by Böhm-Bawerk to pave the way for Fetter's own theory of interest! Of particular importance in this 1927 essay is Fetter's critique of Alfred Marshall's capital theory. Always an unsparing logician, Fetter relentlessly criticized the myriad of inconsistencies, confusions, and contradictions in Marshall's discussion. Fetter also added to his previous criticisms of Fisher's capital theory a review of the inconsistency in adopting a wealth-at-one-time/services-at-one-time distinction between capital and income on top of his previous stock/flow dichotomy. Fetter's contribution entitled "Capital," which appeared in the Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (1930-35), is a convenient summation of his views on capital as well as his criticisms of alternative theories. It is clear that his exclusive concern with capital as a fund, or as "the market value [of] the present worths of… individual claims to incomes," is a consequence of his dissatisfaction with the productivity theories of interest and his desire to establish "capital value" as simply the capitalized sum of expected future rental incomes. Frank A. Fetter's pioneering development of the pure time-preference theory of interest began with his article "The 'Roundabout Process' in the Interest Theory" (1902). Here Fetter hailed Böhm-Bawerk as the first to state properly the central problem of interest theory: To explain why present goods are valued more highly than future goods. But after starting out with time-preference as the proper explanation, Böhm-Bawerk introduced his "third ground" for interest — the greater productivity of roundabout processes of production — and argued that it was the most important reason present goods had higher values than future goods. When offering his detailed critique of Böhm-Bawerk's "third ground," Fetter explained how Böhm-Bawerk had failed to separate the undoubted increase in physical productivity, resulting from an increase in capital, from a claimed increase in the "value" productivity of capital. Fetter noted that an increase in the value of capital (as distinct from its physical amount) will increase the value productivity of capital if and only if the interest rate remains constant. In other words, Böhm-Bawerk's productivity explanation of interest makes use of the concept of the present value of capital and therefore assumes that the interest rate is already given, since it is needed to determine the present value of capital. Thus, Böhm-Bawerk's productivity explanation of interest involved circular reasoning. Similarly, Fetter noted that one determinant of the degree of capitalization, or the degree of roundaboutness of production processes in the economy, is precisely the interest rate — the rate of present capitalization of future rents. Here is still another example of circular reasoning. For the remainder of his 1902 article, Fetter elaborated on his critique (outlined above) of the Austrian separation of land and capital goods, and the idea of the period of production. Here it might be noted that Fetter's perfectly valid point about land capitalization in the market by way of the interest rate does not negate the Austrian distinction between land and capital goods. According to the Austrian school "capital" and "capital goods" are separate and distinct concepts. Furthermore, Fetter's repeated attempts to attribute a labor theory of capital value to Böhm-Bawerk are contradicted by his own admission that both land and time enter into the Austrian view of the production of capital. Fetter, however, made an important point in criticizing Böhm-Bawerk's formulation of the "average period of production," especially the idea of ex post averaging of the various periods of production throughout the economy. Fetter also cogently attacked Böhm-Bawerk's attempt to leap from the increased physical productivity of roundabout processes to value productivity by the use of purely arithmetical tables. Here Fetter leveled a (characteristically Austrian) critique of the use of mathematics in economics against an economist who was himself a leading critic of the mathematical method. In his 1902 article, Fetter offered another brilliant criticism of Böhm-Bawerk's "third ground." Böhm-Bawerk tried to use the greater productivity of capital to explain why these "present goods" are worth more than "future goods" when the capital comes to fruition as consumer goods. But, as Fetter pointed out, since capital instruments only mature into consumer goods at various times in the future, capital goods are really future goods, not present goods. If, then, we concentrate on utility to consumers, capital goods are seen to be future goods, and the "third ground" for an extra return to these (future) capital goods as being more productive "present goods" becomes totally invalid. We may apply Fetter's insight to the current textbook explanations of interest rate determination in the market for productive loans. The supply curve of loanable funds is conventionally explained by time-preference, while the demand curve for loans by business firms is explained by reference to the "marginal productivity of capital" — in short, by the "natural" rate of interest embodied in the long-term normal rate of profit. But the firm that borrows money in order to hire workers or to buy capital goods is really buying future goods in exchange for a present good, money. In short, the business borrower, like the saver-creditor who lends him money, is buying a future good whenever he makes an investment. If we assume, for example, that there are no business loans but only stock investment, this point is easier to understand. When a man saves and invests in a productive process, he pays workers and other factors now in exchange for services that will yield a product, and therefore an income, at some future time. In short, the capitalist-entrepreneur hires or invests in factors now and pays out money (a present good) in exchange for productive services that are future goods. It is for his service in paying factors now, in advance of the fruits of production, that the capitalist normally earns an interest return, a return for time-preference. In sum, every factor of production (whether labor, land, or capital goods) earns, not its marginal value productivity, according to the current conventional explanation, but its marginal productivity discounted by the interest rate or time-preference; and the capitalist earns the discount. Fetter also cogently argued that Böhm-Bawerk in effect used one explanation (the "third ground") for interest on producer goods and another (the notion of time-preference) for interest on consumer loans. Since interest must have a unitary explanation, Böhm-Bawerk's analysis is something of a retrogression. Fetter stressed the basic weakness of all productivity explanations of interest. It is not enough, he pointed out, to show that more capital is productive in physical or even value terms; the problem is to explain why the value of capital on the market today is low enough to generate a surplus value return tomorrow. The productivity of capital has nothing to do with the solution to this problem. As Fetter wrote:

Fetter pointed out ironically that Böhm-Bawerk himself, in criticizing earlier productivity theories of interest, had raised precisely the same point. Even conceding that very long roundabout processes may be physically highly productive, Fetter pointed out that the question remained unresolved in Böhm-Bawerk why these processes are not then always preferred to less productive, but more immediately fruitful, processes. Fetter concluded by reiterating his unique position on the relationship between interest and rent. Rent reflects the (marginal) productivity of scarce factors of production, and interest reflects the present valuation of future services and therefore depends, not at all on roundaboutness, but on the postponement of use. The theory of interest, Fetter concluded, "must set in their true relation the theory of rent as the income from the use of goods in any given period, and interest as the agio or discount on goods of whatever sort, when compared throughout successive periods." In the presentation of his theory before the American Economic Association, "The Relations between Rent and Interest" (1904), Fetter pointed out the confusions and inconsistencies of previous writers on the theory of rent and interest. In place of the classical distinction between rent as income from land and interest as income from capital goods, Fetter proposed that all factors of production, whether land or capital goods, be considered either "as yielding uses,… as [a] bearer of rent," or as "salable at their present worth,… as [a] discounted sum of rents," as "wealth" or "capital." As a corollary, rent must be conceived of as an absolute amount (per Unit time), whereas interest is a ratio (or percentage) of a principal sum called capital value. Rent becomes the usufruct from any material agent or factor — the use of the agent considered apart from using it up. But then there is no place for the idea of interest as the yield of capital goods. Rents from any durable good accrue at different points in time, at different dates in the future. The capital value of any good then becomes the sum of its expected future rents, discounted by the rate of time-preference for present over future goods, which is the rate of interest. In short, the capital value of a good is the "capitalization" of its future rents in accordance with the rate of time-preference or interest. Therefore, marginal utility accounts for the valuations and prices of consumer goods; the rent of each factor of production is determined by its productivity in eventually producing consumer goods; and interest arises in the capitalization, in accordance with time-preference, of the present worth of the expected future rents of durable goods. Such is Fetter's lucid, systematic, and unique vision of the relative place of rent, interest, and capital value in the theory of distribution. Fetter's paper was considered so important that nine economists were assigned to discuss it. As Fetter indicated in his reply, few of his commentators demonstrated that they understood his positive theory, and many were only interested in defending the classical school against Fetter's criticisms. To Thomas Nixon Carver's major point that since land, in contrast to other factor services, need not be supplied, land rent does not enter into cost, Fetter replied: (1) that the same sort of surplus, or no-cost, elements may be said to permeate all factors of production, and (2) that land, like other factors, must also be served, maintained, and allocated efficiently. Furthermore, several of the commentators, as Fetter pointed out, mistakenly identified Fetter's theory with that of John Bates Clark and proceeded to criticize Clark's assimilation of rent and interest, despite the fact that Fetter held an almost diametrically opposed view. A decade later Fetter returned to the theory of interest, in "Interest Theories, Old and New" (1914), as part of a critique of Irving Fisher's recantation from his previous adherence to pure time-preference theory, a position he had approached in his The Rate of Interest (1907), and one that influenced Fetter in developing his own theory. But now Fisher was taking the path of Böhm-Bawerk and returning to a partial productivity explanation. Moreover, Fetter discovered that the seeds of error were in Fisher's publication of 1907. Fisher had stated that valuations of present and future goods imply a preexisting money rate of interest, thereby suggesting that a pure time-preference explanation of interest involves circular reasoning. By way of contrast, and in the course of explaining his own pure time-preference, or "capitalization," theory of interest, Fetter showed that time valuation is prerequisite to the determination of the market rate of interest. The market rate of interest on loans is, for Fetter, a reflection of a general rate of time-preference in the economy, a capitalization process that discounts, in the present prices of durable goods and factors of production, the future uses of these goods. Consumers evaluate directly enjoyable consumer goods, then evaluate durable factors according to their productivity in making these goods, and then discount these future uses to the present in accordance with their time-preferences. The first step yields the prices of consumer goods; the second, the incomes or rents of producer goods; the last, the "underestimation" of, or the rate of interest yielded by, the producer goods. Again restating his case, this time in criticizing the views of Henry R. Seager, Fetter pointed to the crucial problem: why does entrepreneurial purchase of factors seem to contain within itself a net surplus, an interest return? The productivity of capital goods does not explain why the value of this expected productivity is discounted in their present price, which in turn permits the entrepreneurs to pay interest on loans with which to buy or hire these factors of production. As Fetter stated: "The amount of interest which 'enterprisers estimate' they can afford to pay... is the difference between the discounted, or present, worth of products imputable to these agents and their worth at the time they are expected to mature." Fetter added that there of course must be productivity to account for the expected future income, just as there must be people and markets; but there would be no rate of interest if the future value of the products were not discounted. Market interest can be paid out of a value surplus that emerges from an antecedent time discount of the "value-productivity" of the factors of production. Or, putting it another way, Fetter readily admitted that productivity of capital goods brings greater value to the final product. "But the value-productivity which furnishes the motive to the enterpriser to borrow and gives him the power, regularly, to pay contract interest, is due, not to the fact that these products will have value when they come into existence, but to the fact that their expected value is discounted in the price of the agents bought at an earlier point of time." Fetter also sharpened the contrast between his own theory and the productivity theory of interest in another way. The productivity theorists assert that as capital grows the economy becomes more productive, and that the interest rate increases owing to the greater productivity of capital. But Fetter countered with the insight that, as the economy advances and more present goods are produced, the preference for present goods is lowered, and the interest rate therefore may be expected to fall. Or, as it might be put more elaborately, everyone has a time-preference schedule relating his supply of present goods with his preference for the present over the future. A greater supply of present goods would move to the right and down along a given time-preference schedule, so that the marginal utility of present goods would fall in relation to future goods. As a result, on the given schedules, the rate of time-preference, of degree of choice of present over future, would tend to fall and so therefore would the interest rate. Fetter also anticipated Frank Knight's classic distinction, in Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit (1921), between interest, or long-run normal profits, on the one hand and short-run profits and losses earned by superior, or suffered by inferior, entrepreneurs on the other — superiority or inferiority defined in terms of the ability to forecast the uncertain future. Why does an entrepreneur borrow at all if in so doing he will bid up the loan rate of interest to the rate of time-preference as reflected in his long-run normal rate of profit (or his "natural rate of interest," to use Austrian terminology)? The reason is that superior forecasters envision making short-run profits whenever the general loan rate is lower than the return they expect to obtain. This is precisely the competitive process, which tends, in the long run, to equalize all natural and loan rates in the time market. Those entrepreneurs "with superior knowledge and superior foresight," wrote Fetter, "are merchants, buying when they can in a cheaper and selling in a dearer capitalization market, acting as the equalizers of rates and prices." Fetter also pointed out, quite correctly, that the process of capitalization and time discount applies as fully and equally to land as it does to capital goods. From the point of view of capitalization, there is no fundamental distinction between land and produced means of production. In fact, Fetter might have pointed out that under slavery, where laborers are owned, they, too, become capitalized, and the present price of slaves becomes the capitalized value of expected future earnings (or "rents") of slaves, discounted by the social rate of time-preference. But the fact that slaves, too, can be capitalized does not justify obliterating for other purposes any and all distinctions between slaves and capital goods. Not only is Fetter's pure time-preference, or capitalization, theory the only one that offers an integrated explanation of interest on slaves, land, and capital goods, but it is also, as he pointed out, the only one that provides an integrated explanation of interest on consumption loans and on productive loans. For even the productivity theorists had to concede that at least in the case of consumer loans interest was occasioned by time-preference. In Fetter's final and extensive treatment of interest, "Interest Theory and Price Movements" (1927), pessimism has replaced his optimism of earlier years; for after an illuminating discussion of early interest theories (in which he rescued Turgot from the deprecation of Böhm-Bawerk), Fetter sadly noted that his insight into interest theory had been ignored. The old productivity theory of interest, having at last conquered Böhm-Bawerk and Irving Fisher, survived as the dominant explanation of interest in the eclectic theory of Alfred Marshall. Among English and American economists, productivity remained the major explanation of interest on productive capital, and time-preference was relegated to an explanation of consumer lending. Fetter proceeded to a particularly extended discussion of the nature of time-preference and the time market. Time-preference enters into primitive, Crusoe-type valuations, which predate the development of barter as well as the emergence of money loans and a money economy. The rates of time-preference reflect all the conditions, the interactions, and the choices of human beings. In almost all cases, present goods are preferred to future goods, and this preference is most marked in primitive man. But, Fetter added, with the development of civilization, the advent of thrift generally means a lowering of the premiums placed on present goods and hence of the rate of time-preference. In the money economy, just as the utility scales of individuals interact to bring about uniform prices on the market, individual time-preference schedules through exchange bring all time-preferences into conformity. The consequence is a social rate of time-preference, a "general, average rate of premium of present dollars over future dollars which has resulted from leveling out a great part of the individual differences." Through arbitrage time-preference rates tend to be equalized throughout the time market. The price of a durable factor of production is derived from the expected price of its products, being the present discount, or capitalized sum, of all of its future products. This capitalization process precedes, rather than follows, the existence of an interest rate on money loans. The time-preference rate that capitalizes future incomes emerges as the long-run normal, or natural, rate of profit of business firms. Short-run deviations from this norm are caused by special circumstances and by entrepreneurial skills. Profit rates tend to be equalized throughout the market through a continuing reevaluation of the prices of durable agents — those capital goods providing a profit being recapitalized upward and those suffering losses being recapitalized downward. This process of recapitalization and reevaluation tends to bring about uniform profit rates, Fetter noted, rather than according to the conventional theory, uniform costs of producing new durable agents. For Fetter, the interest rate on productive money loans and the normal rate of profit tend to equality because they have a common cause: capitalization of time-preferences throughout the time market. As Fetter stated:

Having thus elaborated his concept of time-preference and the time market, Fetter applied his pure theory to the complexities of determining interest in the real world. In the first place, interest rates, in addition to being determined by time-preference, vary in accordance with different degrees of risk, entrepreneurial skill, the cost of making loans, different habits, and legal restrictions. Furthermore, as Fetter pointed out, changes in the price level slow up the market process of equilibrating interest rates and lead to widespread errors of overcapitalization and undercapitalization. In a discussion of money and price levels in relation to the interest rate, Fetter incorporated into his analysis Fisher's insight, now being rediscovered, that interest rates tend to rise during a boom and fall during a recession in response to expected changes in price levels. Rising price levels lower the purchasing power of the creditor's return, and interest rates tend to rise during inflations to compensate for this loss. Conversely, interest rates tend to fall below time-preference rates during a recession to offset the increased real rate of return. But Fetter was not content to stop there. Noting that empirically interest rates do not rise continually during booms, Fetter developed a monetary theory of the business cycle, one that came close to the Mises-Hayek "monetary malinvestment" theory that was being developed in Austria at about the same time (see my America's Great Depression). Fetter explained that a currency inflation from increased government spending raises the price level, which in the long run is determined by movements in the supply of money. But increasing the money supply via bank credit expansion has far more complex consequences. Continuing bank credit expansion not only will bring about a boom and higher prices but also will increase the money supply via a massive increase in the supply of loanable funds emitted by the banks. The increased money supply will keep the rate of interest below the free-market rate, at least until later stages in the boom, and will bring about an overcapitalization of durable and producers' goods. Owing to the increase in product prices combined with the artificially low rates of interest, businessmen are led into numerous unsound investments. When the banks are finally forced to stop their credit expansion, the overestimation of capital values is suddenly reversed, and the boom is quickly succeeded by a recession. Business failures, monetary losses, and lowering of capital values bring the various parts of the system of prices and values on the market once more into harmony. In particular, that part of the market not influenced by bank credit is brought into harmony with the remainder of the economy. Such is the function of the recession in response to the distortions generated by the bank credit expansion of the preceding boom. Criticizing the theory that bank credit should simply be responsive to the "needs of business," Fetter properly pointed out that during a boom business overestimates its "needs" in response to rising prices and the seemingly greater opportunities for profit. In this way, bank credit expansion stimulates those very business "needs" that are supposed to furnish a rigorous criterion for bank credit policy. Fetter also provided a useful critique of the Swedish economist Knut Wicksell's theory that if banks should continue to hold the interest rate below the natural, or free-market, rate, the price level would rise indefinitely. Fetter pointed out that this could only be true if the lowering of the discount rate was accompanied by a continuous expansion of bank credit. Fetter concluded this discussion of interest theory by applying it to the economics of war. During wartime there is a sharp increase in rates of time-preference, in the demand for present goods immediately usable for war purposes. Consequently, there is a substantial rise in wartime of free-market interest rates. Fetter was therefore highly critical of the common attempts by governments to keep interest rates low during wartime, thus creating economic distortions and preventing high interest rates from smoothly shifting resources from civilian industries to war industries, which have a higher immediate demand for funds. Fetter's major article on the theory of rent, "The Passing of the Old Rent Concept" (1901), was one of his most notable essays. It is a detailed critique of the several mutually contradictory rent theories found in Alfred Marshall's Principles of Economics. First is the Ricardian notion that rent is the return to land. The problem of "explaining" rent becomes equivalent to defining what land is and why it is different from capital. Fetter attacked the distinction made between land and capital by criticizing the idea that land can be distinguished from capital in terms of its alleged inelasticity of supply. Fetter argued that both land and capital can be increased in the long run, while in the short run the supply of capital goods can be as inelastic as the supply of land. Fetter next turned his attention to the influential doctrine of quasi-rents. According to Marshall, land (as well as other nonreproducible goods, such as paintings and rare jewelry) is permanently fixed in supply and therefore earns a true rent. Capital goods, however, are fixed in supply only in the short run, and therefore their income, while similar to land rent, is only temporary, hence the term "quasi-rent." Fetter uncovered the crucial error in Marshall's claim that quasi-rents are not part of the cost of production. In making this claim, Marshall had quietly shifted his discussion from the entrepreneur to the owner of the capital good who "earns an income" rather than "pays a cost." Thus instead of being a costless surplus to the entrepreneur, rent "is essentially that payment which, as a part of [money] costs, prevents the [entrepreneur] from getting any surplus which can be attributed to the rented agents." At the base of the Marshallian error in the quasi-rent doctrine, stated Fetter, is a confusion between money costs and the rather mystical concept of "real costs." Money costs of production do not consist of "real" costs; they are simply the market value of the factors of production that the business firm contracts to put to use. To make rent a "surplus" over real cost is tantamount to abandoning the basic notion of rent as a regularly accruing income produced by way of market exchange. Fetter criticized Marshall's adherence to the classical notion that rent is the one income payment that does not enter into the money cost of production, or into the supply price of factors of production. Fetter noted that the rent of land enters into money costs as does any other contractual payment, as any land-renting farmer or businessman can attest. The Marshallian reply that land is employed up until the no-rent margin and therefore has no effect on decisions to produce a little more or less of the product is dismissed by Fetter's demonstration that the same could be said about any factor payment whatsoever by way of generalizing the law of diminishing returns into the law of variable proportions. There is simply nothing special about land rent in this regard. Furthermore, Fetter pointed out that no producer ever pushes a factor as far as the "no-rent" margin; here economic reality contradicts the infinitesimally small units of mathematical economics. For so long as a factor remains productive at all, it will pay a rent in accordance with that productivity, no matter how small. And, furthermore, the supply of any good is determined fully as much by rent-bearing as by marginal units. In sum, land is priced in the same way as labor or capital in terms of the value of its marginal product. In his "Comment on Rent under Increasing Returns" (1930), Fetter demolished the idea of increasing returns and called for an extension of the concept that rent accrues to land to the notion that rent accrues to the separable uses of any kind of durable good whatsoever. Finally in his article on "Rent" in the Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, Fetter traced the history of the notion of rent and defined rent in the common-sense meaning of "renting-out": the amount paid for the separable uses of a durable agent "entrusted by the owner to a borrower, to be returned in equally good condition." It may be that the hallmark of Frank A. Fetter's approach to economic theory was his "radicalism" — his willingness to discard the entire baggage of lingering Ricardianism. In distribution theory his most important contributions are still too radical to be accepted into the corpus of economic analysis. These are: (1) his eradication of all productivity elements from the theory of interest and his development of a pure time-preference, or capitalization, theory and (2) his eradication of everything pertaining to land, whether it be scarcity or some sort of margin over cost, in the theory of rent, in favor of rent as the "renting out" of a durable good to earn an income per unit time. Guided by Alfred Marshall and by eventual retreats toward the older view by Böhm-Bawerk and Fisher, microeconomic theory has chosen a more conservative route. Despite the attention and the enthusiasm accorded to his writings at the time, Fetter's contributions to distribution theory have fallen into neglect and disuse. It is to be hoped that this collection of essays will bring Fetter's contributions and his lucid and systematic economic vision to the attention of contemporary economists. | ||

| And Now for a Really Bad Response to Political Calamity: Autarky Posted: 14 Apr 2022 10:00 AM PDT The world is in chaos, so politicians MUST do something. Hence, they demand autarky, which is like attempting to put out a fire by pouring gasoline on it. Original Article: "And Now for a Really Bad Response to Political Calamity: Autarky" This Audio Mises Wire is generously sponsored by Christopher Condon. | ||

| The Fed Wanted Inflation, Now They Have No Idea What to Do Posted: 14 Apr 2022 09:15 AM PDT In this episode of Radio Rothbard, Ryan McMaken and Tho Bishop take a look back at previous statements by current members of the Fed. For years, the Fed said the biggest problem was a lack of inflation. Now, with inflation at historic heights, is there any reason to believe the Federal Reserve is prepared for what to do next? Recommended Reading"The Fed Who Cried Growth" by Jonathan Newman: Mises.org/RR_77_A "We Still Haven't Reached the Inflation Finale" by Brendan Brown: Mises.org/RR_77_B "Real Wages Fall Again as Inflation Surges and the Fed Plays the Blame Game" by Ryan McMaken: Mises.org/RR_77_C "Do Inflationary Expectations Cause Inflation? Contra Krugman, the Answer Is No" by Frank Shostak: Mises.org/RR_77_D "The Fed Can't Fix the Economy, but It Can Break It" by Jon Wolfenbarger: Mises.org/RR_77_E "Kashkari Said What?" by Robert Aro: Mises.org/RR_77_F Understanding Money Mechanics by Robert P. Murphy: Mises.org/BobMoney Be sure to follow Radio Rothbard at Mises.org/RadioRothbard. | ||

| Political Upheaval Is Not Threatening “Our Democracy.” Our Democracy Is. Posted: 14 Apr 2022 09:00 AM PDT Attempting to understand the political polarization and dysfunction that has increasingly come to define American politics in the twenty-first century requires grappling with a host of interconnected phenomena. The gradual transformations undergone by the Republican and Democratic parties, which saw the steady elimination of liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats, have deep historical roots. For all its apparent complexity, however, our political dysfunction largely stems from a small set of easy-to-understand problems. We must, therefore, resist the popular urge to attribute polarization to specific figures, such as Trump or Obama, and instead look at the structural reasons these figures emerged when they did and into what environment. History, as Scott Horton says, didn't start this morning. Single-Winner, First-Past-the-Post DistrictsThe problem is, in part, an inherited one. For all their ingenuity and creativity in crafting an experimental new kind of government, the Founders directly adopted the British system of elections at the district level. This was understandable, there being few if any applicable historical or contemporary examples they could look to for guidance, and this feature of the British electoral model apparently worked fine. And in a parliamentary system, where the effective head of government is the de facto leader of a majority coalition in parliament, the model can and does work fine. In presidential systems not so much. This has always been a bug more than a feature. And as the American political scientist Lee Drutman has documented, it is telling that while many governments around the world have amended their electoral rules, switching from single-winner, first-past-the-post districts to split-member proportional districts, none have made the switch from the latter to the former. Uncompetitive DistrictsDue to a combination of geographical sorting and gerrymandering, 94 percent of Congressional districts in the United States are now what political scientists designate as uncompetitive. This means one party enjoys so much local popular support it de facto controls that congressional seat. In these districts, the greatest threat therefore comes from a candidate's own party—typically from farther right or left depending on whether the district is Republican or Democrat controlled. This effectively means the winner of that party's primary becomes the de facto congressional representative for the district. As political participation fell across the board from the 1970s through the 2000s, primary voter turnout fell with it. Today, just 28 percent of registered voters nationwide turn out on primary day—up from 14 percent a decade ago. Those who turn up are generally the most ideologically committed partisans of their parties and they effectively choose upwards of 90 percent of Congress's members. Unsurprisingly, under these conditions it was increasingly the most partisan of their parties each sent to Congress. The Nationalization of ElectionsThis was essentially the ideological purification of brands. As the geographical sorting and ideological party realignments of the 1960s–90s documented by Alan Abramowitz unfolded, party leaders increasingly sought to distinguish their party by emphasizing its ideological commitments. The strategy, pioneered by Newt Gingrich, sought to replace discussions of local issues with the major issues separating the two national parties as the dividing lines in local races. Because the two parties were increasingly distinct both ideologically and demographically, along urban/rural, college educated / blue collar, secular/Christian, nonwhite/white, political fights at the national level came increasingly to be about the character of the country itself. Under such circumstances, the stakes involved are perceived to dramatically increase. For, unlike distributional questions, questions of national identity cut to who we are and what are values are. Combined with a uniquely competitive electoral environment, politics has increasingly come to resemble warfare rather than reasoned debate. Insecure MajoritiesAbout that newly competitive electoral environment, as Frances Lee outlined in her important book insecure majorities were a relatively rare occurrence in American politics in the twentieth century. From the Civil War onward Republicans essentially dominated the White House and Congress until FDR's landslide, which ushered in a period of Democratic dominance. From the end of the Second World War until 1994, Democrats controlled the House for forty-five of forty-nine years—with the Senate much of the time as well. When one party enjoys such broad support, the dynamics of negotiations between parties are fundamentally different than when either party could find itself in power come next November. Where much of the twentieth century saw minority parties positively collaborating in the legislative process, using what power they had to pragmatically shape legislation more to their liking, American politics in the twenty-first century has been defined by strategic opposition—betting, in effect, that fiercely opposing your opponent's legislative initiatives will prove more popular with your own voters than will making compromises to govern more effectively. The Growth of GovernmentDemocracy in America, in the Tocquevillian sense, evolved naturally out of deeply rooted social, economic, and political interrelations at the local level. But for much of its history "democracy," in the modern parlance of one person one vote, was not practiced in the United States. Real universal suffrage arrived late, in the 1960s. It brought with it subsequent enlargements of a federal government already too big, and it was this expansion, perhaps more than anything else, that destroyed the foundations of democracy in America. First, politics gradually ceased being local. The growing power and wealth concentrated in Washington led naturally to an alienation of the people from the power that they collectively supposed to be theirs. And the people's collective faith in their government, by any number of metrics, steadily declined from the 1960s onward. Second, the expansion of the government obviated the purpose of most of the prior institutions of civil society, the very foundations of democracy. Schools were placed under the purview of Washington, while the many mutual aid societies and church groups central to community life were outright replaced or marginalized. Citizens were torn from their collective institutions, placed at home, and told to write a letter to their representative or donate to one or the other party. The truth is that over the course of the twentieth century, America gradually traded democracy for statism. ConclusionWhile there are other factors that bear consideration—and some, like the centralization of party leadership and the increasing influence of corporate lobbying over the legislative and electoral processes, bear significant shares of the blame—these five interconnected issues are most to blame for the dysfunction that has made America's once enviable government a laughingstock the world over. While the process was a gradual one, and therefore passed largely unobserved, today historians of American politics can clearly delineate the development of this trend towards less pragmatic politics: for in a political incentive structure where candidates feel most answerable to their own party's most radical partisans, what incentive is there to compromise in order to govern more effectively? Answer, unless you believe politicians are solely guided by pursuit of the public good, rather than with an eye toward their own chances at reelection, none. In case you are in any doubt, as a GOP strategist succinctly explained: "If the purpose of the majority is to govern, then the purpose of the minority is to become the majority." Though it is obvious something must be done, because any change to the status quo would threaten the collective monopoly on power they have long enjoyed, Republicans and Democrats predictably oppose even mild attempts at reform, such as rank choice voting—let alone the more radical but desperately needed switch to multimember proportional districts. We are therefore likely to see only more increasingly desperate efforts by both Democrats and Republicans to capture the state, producing more dysfunction—until, finally, the system fails completely. This posting includes an audio/video/photo media file: Download Now | ||

| Posted: 14 Apr 2022 08:15 AM PDT Russian oligarchs, American pols, and state-connected billionaires are all cut from the same cloth: they didn't earn, or fully earn, their wealth and position in society. We must withdraw our sanction of these people. Original Article: "The Wrong Elites" This Audio Mises Wire is generously sponsored by Christopher Condon. | ||

| How Russia Uses Immigration and Naturalization to Grow State Power Posted: 14 Apr 2022 07:45 AM PDT While the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's expansion has been a central issue in the Russian decision to go to war with Ukraine, this is certainly not the only issue. Moscow has repeatedly maintained that a central factor in its decision was the protection of ethnic Russian minorities in eastern Ukraine from human rights abuses committed by the Ukrainian state. This justification for military intervention has used more than once in recent decades. We saw similar tactics used in Abkhazia and South Ossetia, both in Georgia. The Russian annexation of the Crimea in 2014 used similar rhetoric. Moreover, the Russian state has justified military interventions on grounds that it was protecting the local political independence and autonomy of these minority groups from their respective states' central governments. Notably, the Russian regime extended citizenship to the populations of the separatist regions in question either before or after the military intervention in each case. This was done by granting passports to the residents of each region en masse, in a process called passportization. Most recently, this has also been done in eastern Ukraine, where passportization—as in Georgia—helped set the stage for military intervention. This use of citizenship and naturalization as a tool of foreign policy helps to illustrate some of the geopolitical implications of the existence of unassimilated ethnic or linguistic minorities within a state's borders. These realities also call into question what are often overconfident assumptions that ethnic minorities will "assimilate" and abandon political allegiances with foreign states. In fact, as the Russian efforts in these areas suggest, the process of assimilation can actually be thrown into reverse, with disastrous results for those who are on the losing end of these changes. A Brief History of PassportizationThe Russian passportization effort stems from an apparent shift in the Russian regime toward incorporating Russian ethnics and other sympathetic groups—and the territories they inhabit—into a de facto or de jure union with the Russian state. Some have attributed this strategy specifically to Vladimir Putin, to whom has been attributed the so-called Putin doctrine of "Once Russian, always Russian." This doctrine, to the extent that it actually exists, is nonetheless heavily constrained by political realities. Even if Moscow has big plans for reclaiming numerous parts of the old Soviet Union, the fact is Moscow does not possess the military capability to do so. The fact Moscow's occupation efforts in Ukraine are limited to the south and southeast is only the latest evidence of this. Rather, efforts to bring new territories under Moscow's sway have only worked in areas where the Russian state has first turned a sizable portion of the local population into Russian citizens via the passportization strategy. The Russians did not invent the idea of basing citizenship on ethnicity or cultural bonds. Broadly speaking, the idea that a regime has duties toward subjects living outside its own geographic jurisdiction is an ancient one. Citizenship and state control have not always been tied to physical location, as they are in the modern system of territorial states. Nonetheless, the Russian state has apparently adapted the notion for modern use. The current passportization tactic began approximately twenty years ago. As explained by the Verfassungsblog:

(Passportization has also been a significant development in Transnistria, a separatist region of Moldova that lies on the southwestern Ukrainian border.) Similar tactics were then used in the Donbas region of Ukraine after 2019: